ELEMENT 4: Health and safety monitoring and measuring

SCOPE OF LEARNING-

Health and safety monitoring and measuring

4.1 Active and reactive monitoring

Make sure your monitoring is actually helpful and not simply a formality.

High-quality monitoring will not only reveal issues, but will also shed light on their root causes and the nature of the adjustments that will be required to rectify them. Inadequate monitoring may alert you that something is wrong without providing insight into the root cause or recommended course of action.

Use the same methods you use to keep tabs on other areas of your business to the monitoring of health and safety.

Time and effort are needed for monitoring. You should prepare for it by allocating sufficient resources and, if necessary, training the relevant personnel in advance. There are some universal health and safety guidelines that should be followed regardless of the size or industry of a company.

Timeliness is essential in monitoring. As with any other business system, it’s preferable to have up-to-the-minute information about your company’s operations rather than historical data.

Reporting your findings to influential people in your organisation will maximise the impact of your monitoring efforts. All your hard work in monitoring could be for naught if the board of directors doesn’t commit to acting on the results.

4.1.1 The differences between active and reactive monitoring

There are numerous types of monitoring, however they are generally classified as either ‘active’ or’reactive’:

Active techniques monitor management arrangement design, development, installation, and operation. They are typically preventive in nature, such as

· routine inspections of premises, plant, and equipment by staff

· health surveillance to prevent health problems.

· planned operation routine inspections of critical plant components

Reactive approaches monitor evidence of poor health and safety procedures, but they can also find improved practises that can be extended to other areas of a business, such as:

· investigating accidents and events

· keeping track of occurrences of illness and

· absence records

Organizational monitoring typically includes the use of performance metrics. One of the most common methods of monitoring is comparing results to a set of benchmarks.

The most important part is deciding which metrics to utilise. If you use the wrong metrics, your company will waste time and resources for no good reason.

Health and Safety Inspections

The term “safety inspection” is commonly used to refer to routine checks of a building or area for potential hazards. In addition to looking for potential dangers and determining how serious they are, safety inspections can also check up on things like how well written safety procedures are followed and whether or not hazards have been corrected.

A safety inspection is a comprehensive review of the current state of affairs in the workplace.

The following should form the basis of the predetermined inspection schedule.

How to make sure everything is checked off and documented during an inspection. It’s crucial to keep track of what happened and when in case it becomes relevant at a later time.

What steps local management and supervision should take to address infractions, and how to take them.

Further inspections may be required after an incident or before a special visit by persons who do not typically operate in the area. An occupational health professional, for example, might need to be part of the inspection team in order to give the necessary expertise.

Notification

While organising an inspection, you must decide who must be informed and whether or not the inspection will be conducted in secret. As a matter of protocol and common politeness, it is customary to give advance notice to the regional manager (especially if the inspector is to be accompanied by a member of the workforce in the area). When conducting a thorough inspection, it may be necessary to rearrange activities in the area to ensure the inspector’s safety. Bad habits may be put to rest and the space cleaned up in preparation for the inspection if everyone is made aware of it.

Unannounced checks every so often will reveal if this is the case. Where unannounced inspections are deemed crucial, they require the backing of upper management to be truly effective.

Timings

The best opportunity for the inspection team to see how things are usually done is during a busy period. This, however, must be weighed against the requirement of direct access to employees for the purpose of answering pressing questions.

Frequency

More regular inspections are recommended at higher risk levels. Some Inspections can be done on daily basis, weekly basis, bi-weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc. based on the frequency decided.

Repeated examinations

The inspection team should have ready access to an up-to-date list of previous noncompliances, along with estimated dates of completion, so that items can be added as they are noticed and deleted as they are checked for completion. The organisation will be able to ensure that it is doing everything in its power to protect the health and safety of the people in the area where work is being performed by actively monitoring and advancing the corrective action taken in response to non-compliances.

The Inspecting Group

The goal of the inspection and the level of risk will dictate the size and make-up of the team. It’s possible for a single individual to conduct an inspection, such as the area’s supervisor. But, adding a senior manager, a safety representative, an employee who works in the region, and a technical specialist could be beneficial. At least one member of the inspection team should be well-versed in the protocols of the workplace and the operation of any machines or tools that will be examined. As with any visitor to a workplace, the inspection team should be given a health and safety briefing/induction.

The inspection crew may need specialised clearance to access certain facilities or procedures, as well as appropriate safety gear. A clear methodology for handling unannounced inspections should be in place to ensure the team complies with the risk controls or safe system of work in every given area.

When conducting an inspection, especially one outside of business hours, the inspection crew must always be informed of the emergency protocols in the region. High-risk regions should only be visited by inspection team members who are properly educated and equipped.

Doing a safety inspection

The inspection should be carried out in accordance with a predefined checklist or method — a broad list of elements or objects might serve as a starting point for the inspection.

A list is not exhaustive, and an effective examination will be adaptable enough to identify any new faults or changes that have arisen since the list was last updated. If the area is broad or complex, there may be some audit sampling, which will most likely be random or risk-based.

A safety examination should determine whether or not:

It is reasonable to expect that anyone in contact with, or near, the plant, machinery, or processes being inspected could:

It would be more secure if the item:

When employees are mobile or frequently work in more than one region, the inspection must consider the hazards they face in each context, including practical difficulties such as using equipment in unfamiliar surroundings.

Safety Sampling

By identifying safety faults or omissions, safety sampling exercises aim to quantify the risk of accidents in a given workplace or during a given process or work activity. Display screen equipment, machinery safety, electrical safety, housekeeping, and personal protective equipment are just few of the areas that can be evaluated with the help of a safety sampling sheet. There is a maximum number of points that can be granted for each factor, and each factor is assigned a numerical value based on its relative importance. The effectiveness of the entire safety programme can be tracked by using such a system, which surveys the entire workplace while zeroing in on a specific threat.

If a company, for example, has many offices, data centres, warehousing, workshops, manufacturing, or service units in different locations, then doing safety sampling exercises at each of these locations is a great way to compare how well they are doing in terms of safety. Directors and senior managers can use benchmarking, the process of comparing data from multiple sites to determine where improvements are needed at the corporate and local levels. Feedback on the current state of the organization’s health and safety arrangements can be obtained through random sampling.

Safety Tours

Logistics of a Tour

Tour arrangements

In order to promote awareness and locate housekeeping issues or more easily noticeable physical risks, tours should be conducted periodically.

There is no mandated frequency for conducting safety tours, but doing so at least once a month is recommended. Depending on the size of the area being toured and the amount of time spent talking about the route, a safety tour could be completed in as little as 15 minutes. What is a reasonable frequency for each work area will depend on the nature of the risks being assessed and the scale of the facility. The whole workplace, not just the high-risk parts, needs to be protected.

The point of a tour is to give visitors an overall impression of the workplace, not to go into great depth about any one piece of machinery or tool. Proactive is the word that should describe safety tours. Managers’ participation in the tours is a great way to show staff that they are committed to making safety a top priority.

Team responsible for conducting safety tours

managers in charge of various aspects of the business, such as those in charge of operations, logistics, and individual departments

individuals responsible for safety, such as a manager or a representative

managers, such as those in charge of a call centre or a welding crew.

If necessary, participants may also include representatives from the department of facilities management.

Conducting Tours

The safety manager could have personnel tasked with the tours return a short checklist tailored to the specifics of the region they’ve just seen. The tour group should function as a unit and assign someone to take notes on what they see and what needs to be done.

The area manager is responsible for keeping track of problems and, if at all feasible, resolving them immediately. The note taker should make a note of who is responsible for taking any necessary next steps and by what date.

The next step is for the safety manager to sign off on the report taken down at the meeting. A copy should be given to each member of the tour group, and another copy should be retained in the site’s safety file. Tour participants should go back to this report the next time they visit the region, marking areas that have been improved and those that still require work.

4.1.3 Reactive monitoring measures and their usefulness

Lagging indicators are commonly used to describe monitoring approaches that are used in response to a problem. The likelihood of accidents has decreased if the trailing indicators are trending upwards. On the other hand, an increase in the likelihood of accidents can be predicted if the lagging signs are trending downward.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that over a period of time the monthly accident rate at a given company steadily decreases (due to various safety improvements introduced in the workplace). If so, this metric is trending in the right direction. This demonstrates how accidents have been less likely as of late. But if the number of accidents is going up, that’s a lagging indication trending in the wrong way.

The results of the past can be seen through lagging indicators. There are a variety of situations for which information can be gathered and reported.

4.1.4 Why lessons need to be learnt from beneficial and adverse events

Applying what you’ve learned requires you to do:

The difficulty of guaranteeing uniform adherence to regulations exists even in management arrangements that have been carefully crafted and refined.

Many businesses learn the hard way that they had mechanisms in place—such as regulations, protocols, or instructions—that may have averted an accident or illness but were not followed.

Many times, these problems have their roots in set-ups that were created without taking human nature into consideration, or in situations where inappropriate behaviour was either tacitly or officially sanctioned by higher-ups.

Common factors when things go wrong

Many similar variables have been uncovered via the analysis of large accidents in high-hazard industries, despite their varied technical origins and labour environments. Related to these elements are:

Organizational failure in these areas can lead to the “normalisation” of significant risks, with potentially disastrous results.

Organisational learning

When it comes to managing health and safety in the workplace, organisational learning is essential. Valuable information can be lost if reporting and follow-up mechanisms are not adequate. This is especially true if a blaming culture discourages employees from reporting near-misses.

The likelihood of a recurrence increases if the underlying reasons of precursor events are not recognised and disseminated within the organisation.

Organizational learning is often stymied by internal hurdles, such as the prevalence of siloed divisions.

Human Aspects

Leaders and managers must be mindful of the human, cultural, and structural barriers that may impede the efficient application of learnt lessons.

4.1.4 The difference between leading and lagging indicators.

Leading and lagging safety indicators provide your business with a better understanding of how possible hazards develop and what you can do to reduce overall risk.

So what are the differences between lagging and leading indicators? How do they vary, where do they overlap, and what advantages do they provide to your organisation? Here’s what you should know.

Lagging Safety Indicators

Indicators of safety that are reported after the fact are considered lagging indicators. Rates of incidents that can be documented, as well as information on the frequency and severity of accidents and near-misses in the workplace. In order to improve workplace safety in the future, firms might use lagging indicators to gain insight into past events.

Leading Safety Indicators

Before accidents happen on the job, leading signs of safety are monitored and assessed. The purpose of leading safety indicators is to provide early warning of impending danger so that preventative measures can be put in place. Staff surveys and safety audits, which evaluate existing processes and procedures to identify potential failure areas, are examples of common leading safety indicators. Pre-employment safety training and routine safety meetings are also useful in pinpointing problem areas and formulating solutions for boosting workplace safety.

Difference between leading and lagging indicators

When it comes to safety, time is the primary differentiator between leading and lagging indicators. Leading performance indicators are measured before problems manifest themselves, and trailing indicators are measured after safety accidents have occurred.

The two types of indicators are measured differently as well, with quantitative trailing indicators and qualitative leading indicators. Leading indicators, on the other hand, try to predict future outcomes based on things like employee feedback and close calls, as opposed to the more traditional lagging indicators like injury rates, fatalities, and worker’s compensation claims. In other words, they hope to aid in future prediction rather than only reporting on the past as is done by lagging indicators.

4.2 Investigating incidents

Incidents, as we saw earlier, are any unanticipated occurrences with the potential to result in injury or property damage at work.

Accidents are a special sort of incident which may result in loss, personal (minor) hurt, serious injury or death. When this does not happen, we say that there was a “near miss.” Accidents, like other types of incidents, may need to be reported to government agencies.

All situations, not only accidents, should be looked into because they can result in death, serious injury, minor harm, or a near miss. Rather of focusing on assigning blame, investigations should be conducted to determine what went wrong so that similar incidents can be avoided in the future.

Each incident or accident necessitates its own investigation. But, looking at all the accidents which may have taken place at work may suggest that some appear to be linked; for example, the history of a number of comparable incidents may indicate a tendency of specific sorts of accident or failures of particular safety measures. So, it is necessary to look at the specifics of the present incident and compare them to previous to see if there is a pattern. This means that the outcomes of all investigations must be summarised and examined, usually using statistical methods.

The organization’s primary goal in investigating and reporting incidents is to eliminate the recurrence of the incident by fixing the underlying and immediate causes. This may entail implementing new protections, processes, training and information, or any combination of these. However, other people outside of the organisation may have various reasons for examining situations; for example:

Evidence of wrongdoing and the culpability of those involved is what law enforcement and insurance claims adjusters are after.

Governments also want to know where and how common accidents and incidents occur so that they may better advise on preventative measures and prioritise where new laws should be enacted. So, it is customary to notify authorities about certain incidents.

There are two sides to the role of investigations:

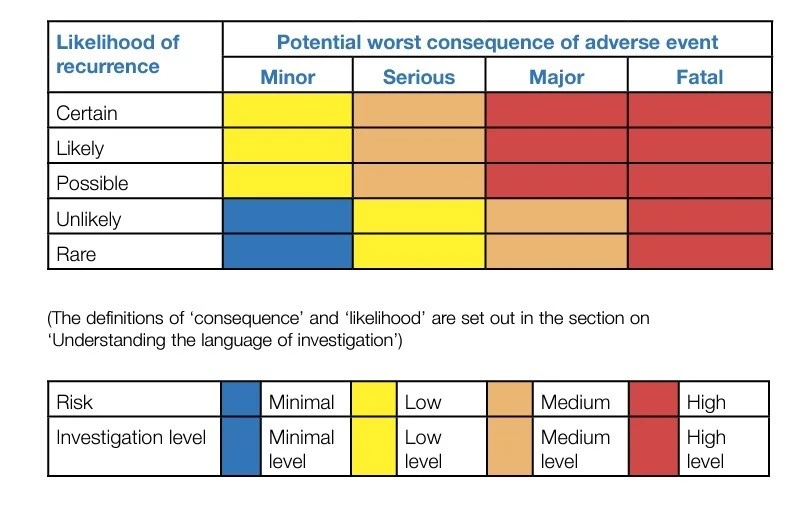

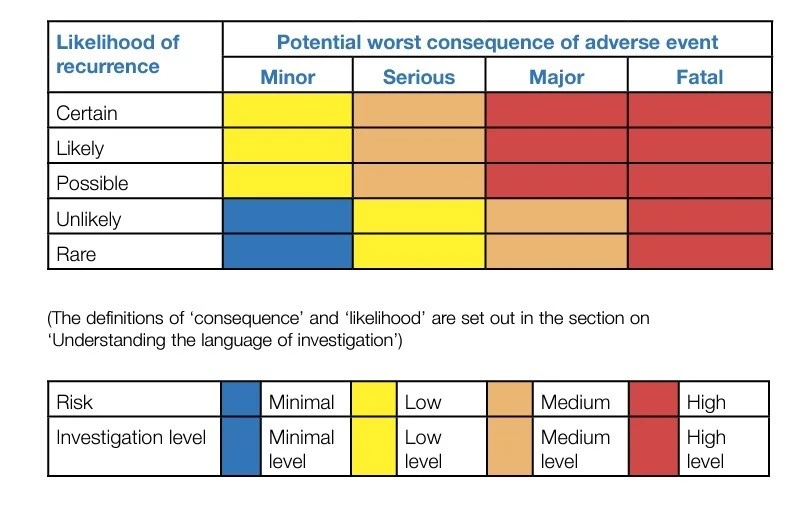

4.2.1 The different levels of investigations: minimal, low, medium and high

The likelihood and consequence categories as discussed in HSG 245 ‘Investigating accidents and incidents’

Consequence:

Fatal: work-related death;

Major injury/ill health: (as defined in RIDDOR, Schedule 1), including fractures (other than fingers or toes), amputations, loss of sight, a burn or penetrating injury to the eye, any injury or acute illness resulting in unconsciousness, requiring resuscitation or requiring admittance to hospital for more than 24 hours;

Serious injury/ill health: where the person affected is unfit to carry out his or her normal work for more than three consecutive days;

Minor injury: all other injuries, where the injured person is unfit for his or her normal work for less than three days;

Damage only: damage to property, equipment, the environment or production losses. (This guidance only deals with events that have the potential to cause harm to people.)

Likelihood that an adverse event will happen again:

Certain: it will happen again and soon;

Likely: it will reoccur, but not as an everyday event;

Possible: it may occur from time to time;

Unlikely: it is not expected to happen again in the foreseeable future; rare: so unlikely that it is not expected to happen again.

Risk: Likelihood of an adverse event and the potential severity of its repercussions (how frequently it is likely to occur, how many people could be harmed, and how severe would the likely injuries or poor health effects be?) are taken into account when assessing the level of risk.

Use the following table to help you decide what kind of investigation is needed for the adverse occurrence. Keep in mind that you have to think about the worst case scenario when dealing with the unpleasant incident (eg a scaffold collapse may not have caused any injuries, but had the potential to cause major or fatal injuries).

In a minimal level investigation, the concerned manager would look into what happened and try to draw any conclusions that would help prevent a repeat performance.

The immediate, underlying, and root reasons of the bad occurrence will be investigated briefly by the relevant supervisor or line manager in a low-level investigation to try to prevent a recurrence and learn any general lessons.

In a medium-level investigation, the relevant supervisor or line manager, the health and safety adviser, and employee representatives conduct a more in-depth inquiry to identify the immediate, underlying, and root reasons.

In a high-level investigation, a group of people, including supervisors or line managers, health and safety consultants, and employee representatives, will work together to get to the bottom of what happened. Finding the immediate, underlying, and root reasons will be the focus of this investigation, which will be conducted under the direction of top management or directors.

4.2.2 Basic incident investigation steps

There is a sequence of numbered questions across the four stages. The information required on the adverse event investigation form is spelt out in great detail here. Numbers of questions here match those on the actual form.

> step one: gathering the information

> step two: analysing the information

> step three: identifying risk control measures

> step four: the action plan and its implementation

Step One: Gathering the information

Determine the cause of the undesirable outcome and the factors that contributed to it. Get going as soon as possible, if not right away. Information should be recorded as quickly as feasible. This prevents it from being tampered with in any way, such as by rearranging the contents or switching out the security personnel. When required, work must be halted and unauthorised entry must be blocked. Get in touch with anyone who could have witnessed the incident or been aware of the circumstances leading up to it. The level of investigation should determine how much time and energy is spent acquiring information. Get your hands on any and all pertinent data you can. This information might be anything from personal anecdotes to detailed descriptions of the surrounding environment and everything in between. An informal report can be written up after this information has been recorded in notes. Save these records for as long as the investigation lasts.

These can be done by following simple steps like:

Using a checklist while gathering the informations can be helpful.

Step Two: Analysing the information

To analyse something means to look at it from every angle and try to figure out what happened and why. There needs to be a comprehensive review of all the data collected to determine what’s necessary and what’s lacking. Data collection and analysis are concurrent processes. New avenues of inquiry that necessitate more data will emerge as the analysis develops. For the research to be complete and unbiased, it must be carried out methodically, taking into account all of the potential causes and effects of the undesirable occurrence.

Experts and professionals in occupational health and safety, as well as any other relevant parties, should participate in the analysis. This collaborative strategy can be quite effective in bringing to light all of the essential causal components.

Most accident reports focus on what happened to cause the injury, but the point of the investigation is to find out what happened. They are not always the same. For example, an injury could be caused by slipping on a wet floor, but the accident could be caused by not putting up a barrier to stop people from walking on the dangerous surface.

The most important part of the investigation is to find the immediate, direct cause of the incident. This is because the same thing could happen again, and steps must be taken to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Accidents are caused, at least in the beginning, by unsafe actions by people and/or unsafe conditions with the machines and equipment used, the way people work, or the way control measures are used. Even though there may be a deeper reason for these actions or situations, it is important to find out what exactly caused the problem.

• Unsafe acts

These are accidents that people in the workplace directly cause or make worse by what they do or don’t do. They include the following things that people do or don’t do, which are sometimes called “active” or “passive” unsafe acts:

· Running a business without permission or in direct violation of certain rules.

· Operating or working at an unsafe speed, like rushing, whether with machinery or with one’s own body.

· Not using safety equipment or making it so that it doesn’t work.

· Using dangerous equipment on purpose.

· Using equipment in a way that is unsafe, like not for what it was made for or without caring about safety.

· Using unsafe ways to do work, like not following safe systems that have already been set up.

· Getting into an unsafe position or posture, like when lifting or carrying things.

· Not wearing safe clothes or personal protective equipment.

· Acting without thinking, like talking to, distracting, teasing, or startling a coworker.

· Not telling anyone about safety problems, like broken guards or small accidents.

· Working while drunk or high, or when you’re too tired or sick to do your job well.

• Unsafe conditions

These are situations where the physical conditions at work or the way people do their jobs directly cause or contribute to the incident. Among them are the following situations:

· Machines that don’t have guards or don’t have the guards that are needed.

· Guarding that isn’t good enough, like not enough height, strength, mesh, etc.

· The use of broken or poorly maintained equipment that puts people in danger.

· Unsafe floors and work surfaces, such as surfaces that are slippery, rotting, or cracked.

· Unsafe systems of work, such as when workers are put in danger by the way they have to do their jobs or by the rules they have to follow.

· Unsafe PPE, like not giving enough or the right clothes, goggles, gloves, masks, etc.

· Housekeeping that isn’t up to par, leading to piles of trash or dirt, blocked traffic routes (especially emergency exits), etc.

· Layout and design of the workplace that makes it unsafe, such as a bad layout of pedestrian and traffic routes that causes traffic jams or not enough space at workstations.

· Unsafe working conditions, such as not enough light or too much glare and reflection, not enough air flow, too much noise, wrong working temperature or humidity, etc.

Step Three: Identifying risk control measures

Failures and potential fixes can be detected with the use of a systematic analytic process. Only the best of these options should be seriously considered for implementation, thus careful evaluation is required. If many risk mitigation strategies are found, an action plan outlining what has to be done, when, and by whom is required. Assigning a person to take charge of this will help keep the implementation schedule on track.

Now that we know what precipitated the incident and why, we can move on to figuring out what can be done to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. The elimination of an incident’s root cause should also eliminate the possibility of future events with the same cause.

Causes that can be addressed quickly include things like missing guards that can be easily replaced or workers who need to be reminded to wear hearing protection. In order to deal with the immediate cause, it may be required to halt the associated activity, machine, etc.

Management must take action on multiple fronts to address underlying and root causes, including:

· Altering standard operating procedures by, for instance, requiring installers to submit their work for inspection before passing it off as complete, or double-checking the accuracy of assembly instructions before sending them out.

· Raising standards of training for safety and competence.

· Enhanced management and oversight.

· Fostering an environment where safety is prioritised.

To prevent a recurrence of the incident and all the issues that contributed to it, the examination of a single incident may lead to the investigation of a range of deeper issues underlying the immediate cause and the implementation of a range of actions.

Step four: The action plan and its implementation

Senior management, who have the authority to make decisions and act on the investigation team’s recommendations, should be involved at this point of the investigation. A thorough inquiry should result in an action plan for implementing additional risk control measures. The action plan should include SMART objectives, which are Specific, Measurable, Agreed Upon, and Realistic, as well as timeframes. Choosing where to intervene necessitates a thorough understanding of the organisation and how it operates. Management, safety specialists, employees, and their representatives should all contribute to a constructive debate on what should be included in the action plan for the risk control measures suggested to be Undertaken. Not every risk-control measure will be implemented, but those given the greatest priority should be implemented as soon as possible. The scale of the danger should determine your priorities (‘risk’ is the possibility and severity of harm). ‘What is critical to ensuring the health and safety of the workers today?’ What can’t wait until tomorrow? How serious is the danger to employees if this risk management strategy is not implemented right away? If the risk is high, you must act quickly. You will undoubtedly have budgetary limits, but neglecting to implement actions to control major and urgent hazards is completely unacceptable. Either reduce the hazards to an acceptable level or cease working. Risk control methods should be prioritised in your action plan for risks that are not high and immediate. Each risk-control measure should be given a timetable and a person designated to oversee its implementation. It is critical that a specific individual, preferably a director, partner, or senior manager, be assigned the responsibility of ensuring that the overall action plan is carried out. This person does not have to undertake the work, but he or she should keep track of how the risk control action plan is progressing. The action plan’s progress should be assessed on a regular basis. Any significant deviations from the plan should be explained and, if necessary, risk control measures postponed. Workers and their representatives should be kept up to date on the contents of the risk control action plan and its implementation status.

4.2.3 How occupational accidents and diseases are recorded and notified by the organization Various countries have varying definitions of what constitutes an occurrence that must be reported to government-appointed organisations. They are all in agreement that fatal accidents must be reported, and they are most likely the only type that is not underreported. We specified the words used for reportable incidents in an earlier element: Occupational Accident, Occupational Sickness, and Dangerous Occurrence. Chemical splashes causing eye injury, scaffold collapse, and occupational cancer caused by asbestos exposure are typical examples.

Many international guidelines on recommended reporting techniques have been established by the International Labour Organization (ILO). The Protocol to the Occupational Safety and Health Convention 1981 (P155) is the primary reference here; it considerably extends on the general reporting standards of Article 4 of the Occupational Safety and Health Convention 1981. (C155).

Recommendation 194 (which identifies the categories of diseases that should be reported to national governments) and a code of practise back it up. These minimal standards, as stated in Element 1, will have legal force in any State that has ratified the applicable Convention.

There will be no extra information provided here that has not previously been mentioned in previous elements. Suffice it to say, incidents may need to be reported to external agencies as soon as possible. It is your responsibility to learn about the reporting requirements of your local government.

ILO has a Code of practice termed as ‘Recording and Notification of occupational accidents and diseases’ which provides relevant guidelines on recording and notification of Incidents and diseases.

Providing information at the corporate level

To ensure that employees can report immediately to their immediate supervisor any situation that they have reasonable justification to believe presents an imminent and serious danger to life or health without fear of retaliation, employers should make arrangements in consultation with employees or their representatives in the enterprise and in accordance with national laws or regulations.

In order for employees to fulfil their reporting obligations for workplace injuries, occupational disease suspicions, commuting accidents, and dangerous occurrences and incidents, employers should make arrangements in consultation with workers or their representatives in the enterprise and in accordance with national laws or regulations.

These arrangements must contain-

information from workers, workers’ representatives, doctors, and other appropriate people about work-related accidents, diseases, dangerous occurrences and incidents in the workplace, and commuting accidents;

the identification of a competent person, when necessary:

Recording arrangements

At the country level

Employers should be required by legislation or regulation at the national level to create and keep records documenting work-related injuries, illnesses, and other potentially hazardous events.

National laws or regulations should specify which data and information must be recorded in order to ensure the systematic collection of all necessary data and information and to provide the methodology for investigating occupational accidents, occupational diseases, dangerous occurrences, and incidents. Standardization of forms is necessary everywhere they are used for this purpose.

At the very least, enterprise-level record-keeping needs to incorporate notification information.

It is not required to notify employees, but national laws or regulations should outline what other information businesses are expected to keep track of. All of the following should follow from this:

In particular, national laws or regulations should outline:

that such records are to be obtained and maintained in such a way that respects the confidentiality of personal and medical data in accordance with national laws and regulations, conditions and practise, and are consistent with paragraph 6 of the Occupational Health Services Recommendation, 1985 (No. 171);

that the content and format of such records; the period of time within which records are to be established; the period of time for which records are to be retained;

At the Employer level

In compliance with national laws or regulations, employers must have measures in place to report work-related injuries, illnesses, and events.

Some things to consider for these plans are:

Employers have an obligation to keep accident, illness, and incident reports (including those involving transportation) easily accessible at all times.

When multiple employees are hurt in the workplace at once, it’s important to keep track of everyone who was hurt.

If they include all the details necessary for recording or are supplemented appropriately, workers’ compensation insurance reports and accident reports to be filed for notification are admissible as records.

Employers should prepare records for inspection and as information for workers’ representatives and health services as soon as possible, but no later than six days after reporting has occurred.

Employees are expected to engage with their employers to ensure that any work-related injuries, illnesses, or other potentially hazardous incidents are properly documented and reported.

It is the responsibility of the employer to provide workers and their representatives with accurate information on:

In order to help workers and employers limit the risk of exposure to such events, employers should tell workers or their representatives about all occupational accidents, occupational diseases, harmful occurrences and incidents in the firm, and commuting accidents.

Notification Arrangements

At Country Level

Procedures for reporting work-related injuries, illnesses, and harmful events, as well as commuting mishaps, should be established and enforced by the relevant authority in accordance with applicable national laws, rules, and customs.

All parties involved in the development and implementation of the procedures, including the competent authority or authorities, public authorities, and representative organisations of employers and workers, should work closely together.

The following entities should be notified of occupational accidents, occupational diseases, commuting accidents, and hazardous occurrences, as appropriate:

At the Employer level

4.3 Health and safety auditing

4.3.1 Definition of the term ‘audit’

Auditing is a time-tested method that was first used in the realm of finance but is now now used to keep tabs on things like quality, environmental, and safety standards. It offers a critical analysis of each area of activity inside an organisation and gives a systematic, recorded, periodic, and objective evaluation of how effectively the management systems are operating.

It has been defined as:

The organised process of gathering unbiased data on the effectiveness, reliability, and efficacy of the overall health and safety management system and developing plans for remedial action.

4.3.2 Why health and safety management systems should be audited

Assuring that:

It offers management verified feedback that the standards and procedures are satisfactory and suggests any necessary modifications. It lets a company to maintain and improve the efficacy of its safety management system, together with performance review.

The audit must be a thorough, systematic, and critical examination of all areas of safety in the organisation being audited in order to meet the extremely broad objectives. This conclusion was reached after taking into account a variety of health and safety management performance criteria, such as:

A “compliance grade” will be determined based on the audit’s evaluation of actual performance relative to each standard as a percentage of complete compliance. This ranking is determined by the responses to several questions about the standard’s intended operation. This set of questions functions similarly to a checklist of items to be handled in regard to the standard, though in the context of an audit, the answers will be evaluations of the degree to which the organisation fulfils the standard. In the next part, we provide some sample questions.

Compliance ratings can be interpreted in different ways depending on the organisation and the type of risks they are up against. The following table, however, provides a rough idea of what the various star ratings could indicate:

85 – 100% Functioning effectively.

65 – 84% Documented and implemented.

50 – 64% Meets minimum requirements.

0 – 49% Requires immediate attention.

Audits are both expensive and time-consuming. So, they are scheduled reasonably infrequently, at most once a year. The frequency will be determined by the specific risks, the rate of organisational change, and the status of compliance.

It is not necessary to do regular audits on all parts of the system. In high-risk industries, regular technical audits are necessary to ensure the reliability of essential risk-control systems. A safety management system (SMS auditing )’s schedule and methodology are detailed in an auditing plan or programme.

4.3.3 Difference between audits and inspections

The term “auditing” is often used interchangeably with “monitoring” and “inspection” when discussing safety management. This is a temptation that must be resisted. Line managers are primarily responsible for conducting monitoring activities, which are performed on a regular or as-needed basis to check for adherence to the organization’s policies and procedures. When auditors from outside the line of command question the validity of established norms and practises and how they are being applied, they are conducting an audit. It is done on a periodic basis and typically involves some sampling and selecting. The auditing process also includes a look at the tracking system. A safety audit is a check on the management of health and safety, just like an annual financial audit is a check on the solvency of the company (that the business has been managed responsibly and cash has not been misused).

The role

Inspections determine if the organization’s safety processes adequately protect the health and safety of its team members.

An inspection is defined in ISO 9000:2015 as “‘determination of conformance to stated standards’ (3.11.7).”

An audit is a more in-depth review of how the organisation controls the health and safety of its team members.

According to the same ISO standards, an audit is “the systematic, impartial, and recorded process of acquiring objective evidence and objectively analysing it to determine the extent to which audit criteria are fulfilled” (3.13.1).

Frequency

There are various types of Inspection, some of which are conducted on daily basis, weekly basis or monthly basis, etc.

But Audits are not that frequent as the process is more complex.

Cost

Generally, Audits are more time consuming and costly than majority of the Inspections. Some Audits may take more than a week to complete.

Structure

An inspection could consist of a cursory check for the presence or absence of compliance. An audit will perform checks on compliance over a longer time frame and look for discrepancies.

The standard inspection response is a yes or no.

Yet, auditing requires numerous steps and many different people. Details about risk assessment, paperwork, and education can all be included. It also specifies how to care for each component of the equipment (and other similar equipment) at each location.

The Team

An Inspection can be performed by a worker, Engineer, Manager or others based on the responsibilities and requirements, but Audits can only be performed by Trained Auditors and in teams.

Area of Interest

Workplace safety risks are primarily what inspectors look for. When conducting an audit, the focus will be on how a company goes about mitigating risks to its employees.

Audits focus on the whole Health and Safety Management system.

The results

The final product of these two methods is very different from one another. A thorough examination will reveal potential health and safety threats. The inspection will reveal the need to improve working conditions and worker safety by installing additional bulbs if there is not enough lighting for a specific machinery operation.

An audit, however, will cover more ground. It will show on a map why the area was poorly lit and what may be done about it. The dangers that could arise in those circumstances were also described. The paper concludes with suggestions for fixing the underlying problem so that no more security holes remain exploitable. Management receives helpful information for making decisions thanks to these audit reports.

4.3.4 Types of audit: product/services, process, system

Product Audits

The purpose of a quality audit of a manufacturing process is to determine if the goals of the process are actually being met. Product audits evaluate the “fitness for use” of a certain product or set of items. It also takes into account whether or not the product or service satisfies the design specifications. An auditing firm might, for instance, check to see if the factory actually follows the product’s code and specification when making it.

Process Audits

Process, activity, and function audits examine the actions taken by a company. The auditor evaluates the process by contrasting it with the specified criteria. The auditor could examine everything from the initial concept to the final product’s quality control measures.

System Audits

The purpose of a system audit is to examine the entire system, including all of the parts and how they work together. It analyses the inner workings of a company. The auditor may examine multiple processes simultaneously, including design, production, quality assurance, and others. The auditor also considers how these processes interact with one another. Consider the interplay between the design phase and production.

4.3.5 Advantages and disadvantages of external and internal audits

The question of whether safety audits should be conducted in-house or by an independent body has been the subject of some discussion. There is no shortage of consultants willing to take on the challenge.

Independent Advisers

One benefit of hiring outside experts to do the audit is that they will be able to provide a more objective evaluation because they have no ties to the company.

It’s conceivable that their level of experience and knowledge exceeds that of all save the largest businesses.

They may be able to make useful comparisons to other businesses based on their own expertise and knowledge of the industry as a whole.

They may be accommodating in how the audit is scheduled and carried out. However, there are constraints:

As they are unfamiliar with the ins and outs of the job and the workplace, it may take them more time at initially to get up to speed on how things work.

The auditing plan they present might not be adapted to the specific requirements of the business.

In comparison to doing it “in-house,” the cost of using them will be higher.

The risk exists that the organisation will allow the consultants to steer the process instead of vice versa.

If the consultants are often switching, there may be no long-term stability.

Clear roles and responsibilities, as well as open communication, can help mitigate the other potential drawbacks of hiring outside consultants.

ELEMENT 4: Health and safety monitoring and measuring

SCOPE OF LEARNING-

Health and safety monitoring and measuring

4.1 Active and reactive monitoring

Make sure your monitoring is actually helpful and not simply a formality.

High-quality monitoring will not only reveal issues, but will also shed light on their root causes and the nature of the adjustments that will be required to rectify them. Inadequate monitoring may alert you that something is wrong without providing insight into the root cause or recommended course of action.

Use the same methods you use to keep tabs on other areas of your business to the monitoring of health and safety.

Time and effort are needed for monitoring. You should prepare for it by allocating sufficient resources and, if necessary, training the relevant personnel in advance. There are some universal health and safety guidelines that should be followed regardless of the size or industry of a company.

Timeliness is essential in monitoring. As with any other business system, it’s preferable to have up-to-the-minute information about your company’s operations rather than historical data.

Reporting your findings to influential people in your organisation will maximise the impact of your monitoring efforts. All your hard work in monitoring could be for naught if the board of directors doesn’t commit to acting on the results.

4.1.1 The differences between active and reactive monitoring

There are numerous types of monitoring, however they are generally classified as either ‘active’ or’reactive’:

Active techniques monitor management arrangement design, development, installation, and operation. They are typically preventive in nature, such as

· routine inspections of premises, plant, and equipment by staff

· health surveillance to prevent health problems.

· planned operation routine inspections of critical plant components

Reactive approaches monitor evidence of poor health and safety procedures, but they can also find improved practises that can be extended to other areas of a business, such as:

· investigating accidents and events

· keeping track of occurrences of illness and

· absence records

Organizational monitoring typically includes the use of performance metrics. One of the most common methods of monitoring is comparing results to a set of benchmarks.

The most important part is deciding which metrics to utilise. If you use the wrong metrics, your company will waste time and resources for no good reason.

Health and Safety Inspections

The term “safety inspection” is commonly used to refer to routine checks of a building or area for potential hazards. In addition to looking for potential dangers and determining how serious they are, safety inspections can also check up on things like how well written safety procedures are followed and whether or not hazards have been corrected.

A safety inspection is a comprehensive review of the current state of affairs in the workplace.

The following should form the basis of the predetermined inspection schedule.

How to make sure everything is checked off and documented during an inspection. It’s crucial to keep track of what happened and when in case it becomes relevant at a later time.

What steps local management and supervision should take to address infractions, and how to take them.

Further inspections may be required after an incident or before a special visit by persons who do not typically operate in the area. An occupational health professional, for example, might need to be part of the inspection team in order to give the necessary expertise.

Notification

While organising an inspection, you must decide who must be informed and whether or not the inspection will be conducted in secret. As a matter of protocol and common politeness, it is customary to give advance notice to the regional manager (especially if the inspector is to be accompanied by a member of the workforce in the area). When conducting a thorough inspection, it may be necessary to rearrange activities in the area to ensure the inspector’s safety. Bad habits may be put to rest and the space cleaned up in preparation for the inspection if everyone is made aware of it.

Unannounced checks every so often will reveal if this is the case. Where unannounced inspections are deemed crucial, they require the backing of upper management to be truly effective.

Timings

The best opportunity for the inspection team to see how things are usually done is during a busy period. This, however, must be weighed against the requirement of direct access to employees for the purpose of answering pressing questions.

Frequency

More regular inspections are recommended at higher risk levels. Some Inspections can be done on daily basis, weekly basis, bi-weekly, monthly, quarterly, etc. based on the frequency decided.

Repeated examinations

The inspection team should have ready access to an up-to-date list of previous noncompliances, along with estimated dates of completion, so that items can be added as they are noticed and deleted as they are checked for completion. The organisation will be able to ensure that it is doing everything in its power to protect the health and safety of the people in the area where work is being performed by actively monitoring and advancing the corrective action taken in response to non-compliances.

The Inspecting Group

The goal of the inspection and the level of risk will dictate the size and make-up of the team. It’s possible for a single individual to conduct an inspection, such as the area’s supervisor. But, adding a senior manager, a safety representative, an employee who works in the region, and a technical specialist could be beneficial. At least one member of the inspection team should be well-versed in the protocols of the workplace and the operation of any machines or tools that will be examined. As with any visitor to a workplace, the inspection team should be given a health and safety briefing/induction.

The inspection crew may need specialised clearance to access certain facilities or procedures, as well as appropriate safety gear. A clear methodology for handling unannounced inspections should be in place to ensure the team complies with the risk controls or safe system of work in every given area.

When conducting an inspection, especially one outside of business hours, the inspection crew must always be informed of the emergency protocols in the region. High-risk regions should only be visited by inspection team members who are properly educated and equipped.

Doing a safety inspection

The inspection should be carried out in accordance with a predefined checklist or method — a broad list of elements or objects might serve as a starting point for the inspection.

A list is not exhaustive, and an effective examination will be adaptable enough to identify any new faults or changes that have arisen since the list was last updated. If the area is broad or complex, there may be some audit sampling, which will most likely be random or risk-based.

A safety examination should determine whether or not:

It is reasonable to expect that anyone in contact with, or near, the plant, machinery, or processes being inspected could:

It would be more secure if the item:

When employees are mobile or frequently work in more than one region, the inspection must consider the hazards they face in each context, including practical difficulties such as using equipment in unfamiliar surroundings.

Safety Sampling

By identifying safety faults or omissions, safety sampling exercises aim to quantify the risk of accidents in a given workplace or during a given process or work activity. Display screen equipment, machinery safety, electrical safety, housekeeping, and personal protective equipment are just few of the areas that can be evaluated with the help of a safety sampling sheet. There is a maximum number of points that can be granted for each factor, and each factor is assigned a numerical value based on its relative importance. The effectiveness of the entire safety programme can be tracked by using such a system, which surveys the entire workplace while zeroing in on a specific threat.

If a company, for example, has many offices, data centres, warehousing, workshops, manufacturing, or service units in different locations, then doing safety sampling exercises at each of these locations is a great way to compare how well they are doing in terms of safety. Directors and senior managers can use benchmarking, the process of comparing data from multiple sites to determine where improvements are needed at the corporate and local levels. Feedback on the current state of the organization’s health and safety arrangements can be obtained through random sampling.

Safety Tours

Logistics of a Tour

Tour arrangements

In order to promote awareness and locate housekeeping issues or more easily noticeable physical risks, tours should be conducted periodically.

There is no mandated frequency for conducting safety tours, but doing so at least once a month is recommended. Depending on the size of the area being toured and the amount of time spent talking about the route, a safety tour could be completed in as little as 15 minutes. What is a reasonable frequency for each work area will depend on the nature of the risks being assessed and the scale of the facility. The whole workplace, not just the high-risk parts, needs to be protected.

The point of a tour is to give visitors an overall impression of the workplace, not to go into great depth about any one piece of machinery or tool. Proactive is the word that should describe safety tours. Managers’ participation in the tours is a great way to show staff that they are committed to making safety a top priority.

Team responsible for conducting safety tours

managers in charge of various aspects of the business, such as those in charge of operations, logistics, and individual departments

individuals responsible for safety, such as a manager or a representative

managers, such as those in charge of a call centre or a welding crew.

If necessary, participants may also include representatives from the department of facilities management.

Conducting Tours

The safety manager could have personnel tasked with the tours return a short checklist tailored to the specifics of the region they’ve just seen. The tour group should function as a unit and assign someone to take notes on what they see and what needs to be done.

The area manager is responsible for keeping track of problems and, if at all feasible, resolving them immediately. The note taker should make a note of who is responsible for taking any necessary next steps and by what date.

The next step is for the safety manager to sign off on the report taken down at the meeting. A copy should be given to each member of the tour group, and another copy should be retained in the site’s safety file. Tour participants should go back to this report the next time they visit the region, marking areas that have been improved and those that still require work.

4.1.3 Reactive monitoring measures and their usefulness

Lagging indicators are commonly used to describe monitoring approaches that are used in response to a problem. The likelihood of accidents has decreased if the trailing indicators are trending upwards. On the other hand, an increase in the likelihood of accidents can be predicted if the lagging signs are trending downward.

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that over a period of time the monthly accident rate at a given company steadily decreases (due to various safety improvements introduced in the workplace). If so, this metric is trending in the right direction. This demonstrates how accidents have been less likely as of late. But if the number of accidents is going up, that’s a lagging indication trending in the wrong way.

The results of the past can be seen through lagging indicators. There are a variety of situations for which information can be gathered and reported.

4.1.4 Why lessons need to be learnt from beneficial and adverse events

Applying what you’ve learned requires you to do:

The difficulty of guaranteeing uniform adherence to regulations exists even in management arrangements that have been carefully crafted and refined.

Many businesses learn the hard way that they had mechanisms in place—such as regulations, protocols, or instructions—that may have averted an accident or illness but were not followed.

Many times, these problems have their roots in set-ups that were created without taking human nature into consideration, or in situations where inappropriate behaviour was either tacitly or officially sanctioned by higher-ups.

Common factors when things go wrong

Many similar variables have been uncovered via the analysis of large accidents in high-hazard industries, despite their varied technical origins and labour environments. Related to these elements are:

Organizational failure in these areas can lead to the “normalisation” of significant risks, with potentially disastrous results.

Organisational learning

When it comes to managing health and safety in the workplace, organisational learning is essential. Valuable information can be lost if reporting and follow-up mechanisms are not adequate. This is especially true if a blaming culture discourages employees from reporting near-misses.

The likelihood of a recurrence increases if the underlying reasons of precursor events are not recognised and disseminated within the organisation.

Organizational learning is often stymied by internal hurdles, such as the prevalence of siloed divisions.

Human Aspects

Leaders and managers must be mindful of the human, cultural, and structural barriers that may impede the efficient application of learnt lessons.

4.1.4 The difference between leading and lagging indicators.

Leading and lagging safety indicators provide your business with a better understanding of how possible hazards develop and what you can do to reduce overall risk.

So what are the differences between lagging and leading indicators? How do they vary, where do they overlap, and what advantages do they provide to your organisation? Here’s what you should know.

Lagging Safety Indicators

Indicators of safety that are reported after the fact are considered lagging indicators. Rates of incidents that can be documented, as well as information on the frequency and severity of accidents and near-misses in the workplace. In order to improve workplace safety in the future, firms might use lagging indicators to gain insight into past events.

Leading Safety Indicators

Before accidents happen on the job, leading signs of safety are monitored and assessed. The purpose of leading safety indicators is to provide early warning of impending danger so that preventative measures can be put in place. Staff surveys and safety audits, which evaluate existing processes and procedures to identify potential failure areas, are examples of common leading safety indicators. Pre-employment safety training and routine safety meetings are also useful in pinpointing problem areas and formulating solutions for boosting workplace safety.

Difference between leading and lagging indicators

When it comes to safety, time is the primary differentiator between leading and lagging indicators. Leading performance indicators are measured before problems manifest themselves, and trailing indicators are measured after safety accidents have occurred.

The two types of indicators are measured differently as well, with quantitative trailing indicators and qualitative leading indicators. Leading indicators, on the other hand, try to predict future outcomes based on things like employee feedback and close calls, as opposed to the more traditional lagging indicators like injury rates, fatalities, and worker’s compensation claims. In other words, they hope to aid in future prediction rather than only reporting on the past as is done by lagging indicators.

4.2 Investigating incidents

Incidents, as we saw earlier, are any unanticipated occurrences with the potential to result in injury or property damage at work.

Accidents are a special sort of incident which may result in loss, personal (minor) hurt, serious injury or death. When this does not happen, we say that there was a “near miss.” Accidents, like other types of incidents, may need to be reported to government agencies.

All situations, not only accidents, should be looked into because they can result in death, serious injury, minor harm, or a near miss. Rather of focusing on assigning blame, investigations should be conducted to determine what went wrong so that similar incidents can be avoided in the future.

Each incident or accident necessitates its own investigation. But, looking at all the accidents which may have taken place at work may suggest that some appear to be linked; for example, the history of a number of comparable incidents may indicate a tendency of specific sorts of accident or failures of particular safety measures. So, it is necessary to look at the specifics of the present incident and compare them to previous to see if there is a pattern. This means that the outcomes of all investigations must be summarised and examined, usually using statistical methods.

The organization’s primary goal in investigating and reporting incidents is to eliminate the recurrence of the incident by fixing the underlying and immediate causes. This may entail implementing new protections, processes, training and information, or any combination of these. However, other people outside of the organisation may have various reasons for examining situations; for example:

Evidence of wrongdoing and the culpability of those involved is what law enforcement and insurance claims adjusters are after.

Governments also want to know where and how common accidents and incidents occur so that they may better advise on preventative measures and prioritise where new laws should be enacted. So, it is customary to notify authorities about certain incidents.

There are two sides to the role of investigations:

4.2.1 The different levels of investigations: minimal, low, medium and high

The likelihood and consequence categories as discussed in HSG 245 ‘Investigating accidents and incidents’

Consequence:

Fatal: work-related death;

Major injury/ill health: (as defined in RIDDOR, Schedule 1), including fractures (other than fingers or toes), amputations, loss of sight, a burn or penetrating injury to the eye, any injury or acute illness resulting in unconsciousness, requiring resuscitation or requiring admittance to hospital for more than 24 hours;

Serious injury/ill health: where the person affected is unfit to carry out his or her normal work for more than three consecutive days;

Minor injury: all other injuries, where the injured person is unfit for his or her normal work for less than three days;

Damage only: damage to property, equipment, the environment or production losses. (This guidance only deals with events that have the potential to cause harm to people.)

Likelihood that an adverse event will happen again:

Certain: it will happen again and soon;

Likely: it will reoccur, but not as an everyday event;

Possible: it may occur from time to time;

Unlikely: it is not expected to happen again in the foreseeable future; rare: so unlikely that it is not expected to happen again.

Risk: Likelihood of an adverse event and the potential severity of its repercussions (how frequently it is likely to occur, how many people could be harmed, and how severe would the likely injuries or poor health effects be?) are taken into account when assessing the level of risk.

Use the following table to help you decide what kind of investigation is needed for the adverse occurrence. Keep in mind that you have to think about the worst case scenario when dealing with the unpleasant incident (eg a scaffold collapse may not have caused any injuries, but had the potential to cause major or fatal injuries).

In a minimal level investigation, the concerned manager would look into what happened and try to draw any conclusions that would help prevent a repeat performance.

The immediate, underlying, and root reasons of the bad occurrence will be investigated briefly by the relevant supervisor or line manager in a low-level investigation to try to prevent a recurrence and learn any general lessons.

In a medium-level investigation, the relevant supervisor or line manager, the health and safety adviser, and employee representatives conduct a more in-depth inquiry to identify the immediate, underlying, and root reasons.

In a high-level investigation, a group of people, including supervisors or line managers, health and safety consultants, and employee representatives, will work together to get to the bottom of what happened. Finding the immediate, underlying, and root reasons will be the focus of this investigation, which will be conducted under the direction of top management or directors.

4.2.2 Basic incident investigation steps

There is a sequence of numbered questions across the four stages. The information required on the adverse event investigation form is spelt out in great detail here. Numbers of questions here match those on the actual form.

> step one: gathering the information

> step two: analysing the information

> step three: identifying risk control measures

> step four: the action plan and its implementation

Step One: Gathering the information

Determine the cause of the undesirable outcome and the factors that contributed to it. Get going as soon as possible, if not right away. Information should be recorded as quickly as feasible. This prevents it from being tampered with in any way, such as by rearranging the contents or switching out the security personnel. When required, work must be halted and unauthorised entry must be blocked. Get in touch with anyone who could have witnessed the incident or been aware of the circumstances leading up to it. The level of investigation should determine how much time and energy is spent acquiring information. Get your hands on any and all pertinent data you can. This information might be anything from personal anecdotes to detailed descriptions of the surrounding environment and everything in between. An informal report can be written up after this information has been recorded in notes. Save these records for as long as the investigation lasts.

These can be done by following simple steps like:

Using a checklist while gathering the informations can be helpful.

Step Two: Analysing the information

To analyse something means to look at it from every angle and try to figure out what happened and why. There needs to be a comprehensive review of all the data collected to determine what’s necessary and what’s lacking. Data collection and analysis are concurrent processes. New avenues of inquiry that necessitate more data will emerge as the analysis develops. For the research to be complete and unbiased, it must be carried out methodically, taking into account all of the potential causes and effects of the undesirable occurrence.

Experts and professionals in occupational health and safety, as well as any other relevant parties, should participate in the analysis. This collaborative strategy can be quite effective in bringing to light all of the essential causal components.

Most accident reports focus on what happened to cause the injury, but the point of the investigation is to find out what happened. They are not always the same. For example, an injury could be caused by slipping on a wet floor, but the accident could be caused by not putting up a barrier to stop people from walking on the dangerous surface.

The most important part of the investigation is to find the immediate, direct cause of the incident. This is because the same thing could happen again, and steps must be taken to make sure that doesn’t happen.

Accidents are caused, at least in the beginning, by unsafe actions by people and/or unsafe conditions with the machines and equipment used, the way people work, or the way control measures are used. Even though there may be a deeper reason for these actions or situations, it is important to find out what exactly caused the problem.

• Unsafe acts

These are accidents that people in the workplace directly cause or make worse by what they do or don’t do. They include the following things that people do or don’t do, which are sometimes called “active” or “passive” unsafe acts:

· Running a business without permission or in direct violation of certain rules.

· Operating or working at an unsafe speed, like rushing, whether with machinery or with one’s own body.

· Not using safety equipment or making it so that it doesn’t work.

· Using dangerous equipment on purpose.

· Using equipment in a way that is unsafe, like not for what it was made for or without caring about safety.

· Using unsafe ways to do work, like not following safe systems that have already been set up.

· Getting into an unsafe position or posture, like when lifting or carrying things.

· Not wearing safe clothes or personal protective equipment.

· Acting without thinking, like talking to, distracting, teasing, or startling a coworker.

· Not telling anyone about safety problems, like broken guards or small accidents.

· Working while drunk or high, or when you’re too tired or sick to do your job well.

• Unsafe conditions

These are situations where the physical conditions at work or the way people do their jobs directly cause or contribute to the incident. Among them are the following situations:

· Machines that don’t have guards or don’t have the guards that are needed.

· Guarding that isn’t good enough, like not enough height, strength, mesh, etc.

· The use of broken or poorly maintained equipment that puts people in danger.

· Unsafe floors and work surfaces, such as surfaces that are slippery, rotting, or cracked.

· Unsafe systems of work, such as when workers are put in danger by the way they have to do their jobs or by the rules they have to follow.

· Unsafe PPE, like not giving enough or the right clothes, goggles, gloves, masks, etc.

· Housekeeping that isn’t up to par, leading to piles of trash or dirt, blocked traffic routes (especially emergency exits), etc.

· Layout and design of the workplace that makes it unsafe, such as a bad layout of pedestrian and traffic routes that causes traffic jams or not enough space at workstations.

· Unsafe working conditions, such as not enough light or too much glare and reflection, not enough air flow, too much noise, wrong working temperature or humidity, etc.

Step Three: Identifying risk control measures

Failures and potential fixes can be detected with the use of a systematic analytic process. Only the best of these options should be seriously considered for implementation, thus careful evaluation is required. If many risk mitigation strategies are found, an action plan outlining what has to be done, when, and by whom is required. Assigning a person to take charge of this will help keep the implementation schedule on track.

Now that we know what precipitated the incident and why, we can move on to figuring out what can be done to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. The elimination of an incident’s root cause should also eliminate the possibility of future events with the same cause.

Causes that can be addressed quickly include things like missing guards that can be easily replaced or workers who need to be reminded to wear hearing protection. In order to deal with the immediate cause, it may be required to halt the associated activity, machine, etc.

Management must take action on multiple fronts to address underlying and root causes, including:

· Altering standard operating procedures by, for instance, requiring installers to submit their work for inspection before passing it off as complete, or double-checking the accuracy of assembly instructions before sending them out.

· Raising standards of training for safety and competence.

· Enhanced management and oversight.

· Fostering an environment where safety is prioritised.

To prevent a recurrence of the incident and all the issues that contributed to it, the examination of a single incident may lead to the investigation of a range of deeper issues underlying the immediate cause and the implementation of a range of actions.

Step four: The action plan and its implementation

Senior management, who have the authority to make decisions and act on the investigation team’s recommendations, should be involved at this point of the investigation. A thorough inquiry should result in an action plan for implementing additional risk control measures. The action plan should include SMART objectives, which are Specific, Measurable, Agreed Upon, and Realistic, as well as timeframes. Choosing where to intervene necessitates a thorough understanding of the organisation and how it operates. Management, safety specialists, employees, and their representatives should all contribute to a constructive debate on what should be included in the action plan for the risk control measures suggested to be Undertaken. Not every risk-control measure will be implemented, but those given the greatest priority should be implemented as soon as possible. The scale of the danger should determine your priorities (‘risk’ is the possibility and severity of harm). ‘What is critical to ensuring the health and safety of the workers today?’ What can’t wait until tomorrow? How serious is the danger to employees if this risk management strategy is not implemented right away? If the risk is high, you must act quickly. You will undoubtedly have budgetary limits, but neglecting to implement actions to control major and urgent hazards is completely unacceptable. Either reduce the hazards to an acceptable level or cease working. Risk control methods should be prioritised in your action plan for risks that are not high and immediate. Each risk-control measure should be given a timetable and a person designated to oversee its implementation. It is critical that a specific individual, preferably a director, partner, or senior manager, be assigned the responsibility of ensuring that the overall action plan is carried out. This person does not have to undertake the work, but he or she should keep track of how the risk control action plan is progressing. The action plan’s progress should be assessed on a regular basis. Any significant deviations from the plan should be explained and, if necessary, risk control measures postponed. Workers and their representatives should be kept up to date on the contents of the risk control action plan and its implementation status.